Evaluating Inclusivity

Abstract

This document explores the methods and frameworks used to evaluate inclusivity in engineering design. An introduction where the responsibilities, benefits, and importance of supporting equality, diversity, and inclusivity—including professional and legal responsibilities, the impact on innovation, and desired longevity—are presented. The key terminology of accessible design, universal design, and inclusive design are discussed with definitions, examples, and summaries. Steps for analyzing inclusivity and accessibility for engineering design are outlined, including product demands, user capabilities, and decision-making. This analysis is then applied to the example of a water bottle.

The learning outcomes for this activity are that by the end of this activity you will be able to:

|

Evaluate an engineering design's ability to function in an inclusive and accessible manner.

|

Estimated time to complete: 20 minutes

Introduction

Inclusivity and accessibility are essential considerations in engineering design. Inclusive design aims to create products, services, and environments that are accessible to and usable by as many people as possible, regardless of age, ability, or circumstance. It is not only about accommodating people with disabilities but also about considering the diverse needs and preferences of all users. Inclusive design focuses on creating products that are flexible, adaptable, and intuitive, providing a positive user experience for everyone.

Engineers should design inclusively for numerous reasons, including:

- Responsibility: Engineers build the world, and by not considering inclusivity, they can unintentionally exclude people from participating in society.

- Professional and personal pride: You may believe that being inclusive is "the right" thing to do.

- Trust in engineers: People expect products to be designed well. Designing products and services that are knowingly discriminatory can be damaging to the profession and harmful to engineers' collective reputation.

- Compliance: Adhering to legal regulations and standards set by engineering professional bodies that mandate inclusive design.

- Innovation: Inclusive design encourages creative problem-solving and innovative products.

- Market Reach and User Satisfaction: Designing for inclusivity can improve user experience and satisfaction.

- Safety: Ensuring usability for all can have critical safety implications.

- Design longevity: Inclusive design often results in more durable and adaptable solutions, avoiding the need for potential future (and costly) redesigns.

Key terminology

Three terms to understand when evaluating inclusivity and accessibility are:

- Accessible design

- Universal design

- Inclusive design

These terms are often used interchangeably, but despite many overlaps, they are different.

Accessible design

Accessible design refers to products, technologies, and interfaces that can be used or "accessed" by people with disabilities (including auditory, cognitive, physical, and visual disabilities). In many cases, it is regulated by law; however, on its own, it often leaves out large portions of the population who do not have a defined or legally recognised disability but could have problems or face barriers preventing them from using the technology.

Universal design

Universal design (UD) ('one-size-fits-all' approach) intends to create products that can be used to the greatest extent possible by as many people as possible, regardless of their abilities or disabilities. Universal design focuses on developing a single solution that does not include adaptations or specialised versions for different preferences or needs.

The Disability Act 2005 defines Universal Design as:

The design and composition of an environment so that it may be accessed, understood, and used:

- To the greatest possible extent

- In the most independent and natural manner possible

- In the widest possible range of situations

- Without the need for adaptation, modification, assistive devices, or specialised solutions by any persons of any age or size or having any particular physical, sensory, mental health, or intellectual ability or disability, and

- Means, in relation to electronic systems, any electronics-based process of creating products, services, or systems so that they may be used by any person.

One advantage of adopting universal design is delivering unexpected benefits for groups of people who are not the primary target of the design. This has been termed the "curb cut effect" (curb cuts are known as "dropped kerbs" in the UK). Curb cuts were originally designed to help people in wheelchairs, but they also benefit people with strollers, bicycles, and shopping carts. The curb cut effect, where a design feature intended for a specific group of people, ends up benefiting a much wider group. (Link to Wikipedia article on the curb cut effect and a link to 99pi podcast on the curb cut effect.)

Inclusive design

Inclusive design encompasses accessible design, but unlike universal design, it embraces multiple versions of the product to allow users to tailor it to their needs. Therefore, on top of accessible design, it looks into aspects such as age, culture, economic situation, education, gender, geographic location, language, or race to determine the best design options.

Summary table

| Aspect | Accessible Design | Universal Design | Inclusive Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Focus | Disabilities | Everyone | Marginalised or excluded groups |

| Approach | Accommodative | Proactive and broad | Collaborative and process-driven |

| Outcome | Meets specific needs | Works for all without adaptation | Equitably addresses diversity |

| Examples | Screen readers, ramps | Curb cuts, lever handles | Culturally sensitive transit systems |

Example to illustrate the differences between the 3 types of inclusive design

A city is designing new benches for a public park.

- Accessible design: Add a separate bench with extra features to accommodate wheelchair users and those with limited mobility. One bench in the park has armrests and a higher seat to make it easier for people with limited mobility to sit and stand, a dedicated spot next to the bench for a wheelchair, and specific signage indicating this bench as "accessible."

- Universal design: Create a single bench design that is usable by everyone without requiring special accommodations. Standard benches are designed with adjustable height and depth, making them comfortable for both tall and short people, with wide, flat surfaces with no barriers underneath allowing a wheelchair to roll up beside the bench. Armrests and a gently sloping seat support people who need help standing.

- Inclusive design: Involve diverse users in the design process to ensure that different needs and preferences are understood and addressed in the final bench design. Feedback from parents with strollers, elderly people, wheelchair users, and children leads to the creation of a modular bench system. Some benches include backrests and armrests, while others are flat and open for those who want flexibility. Designs consider cultural preferences, such as ensuring the bench materials do not overheat in sunny climates.

Analysing the inclusivity of a design

It is important to remember that accessibility and inclusivity should not only be considered after the design is finalised and sent to full-scale production. They should be considered throughout the design process. Accessibility and inclusivity should be included in the initial phases of the design process, where the context of the problem is understood, the design and user criteria are defined, and the conceptual design section is performed. Once a final conceptual design has been selected and the detailed planning to turn the idea into a product has been completed, an evaluation of its inclusivity should be conducted. Evaluating inclusivity is also a useful technique to apply to products or services that you have not designed. Once you have reviewed the inclusivity of your design, you may conclude it can be improved by making changes or adaptations.

Evaluating the inclusivity of a design should consider whether principles of Universal Design can be adopted. A systematic process of steps can be followed. The first step would be to analyse who the actual customers are and what groups of potential users might be overlooked. Doing this before committing to a specific design is crucial for user-centred design practice and allows the designer to make the product truly inclusive for as broad a group of people as possible.

Steps for analysing inclusivity and accessibility

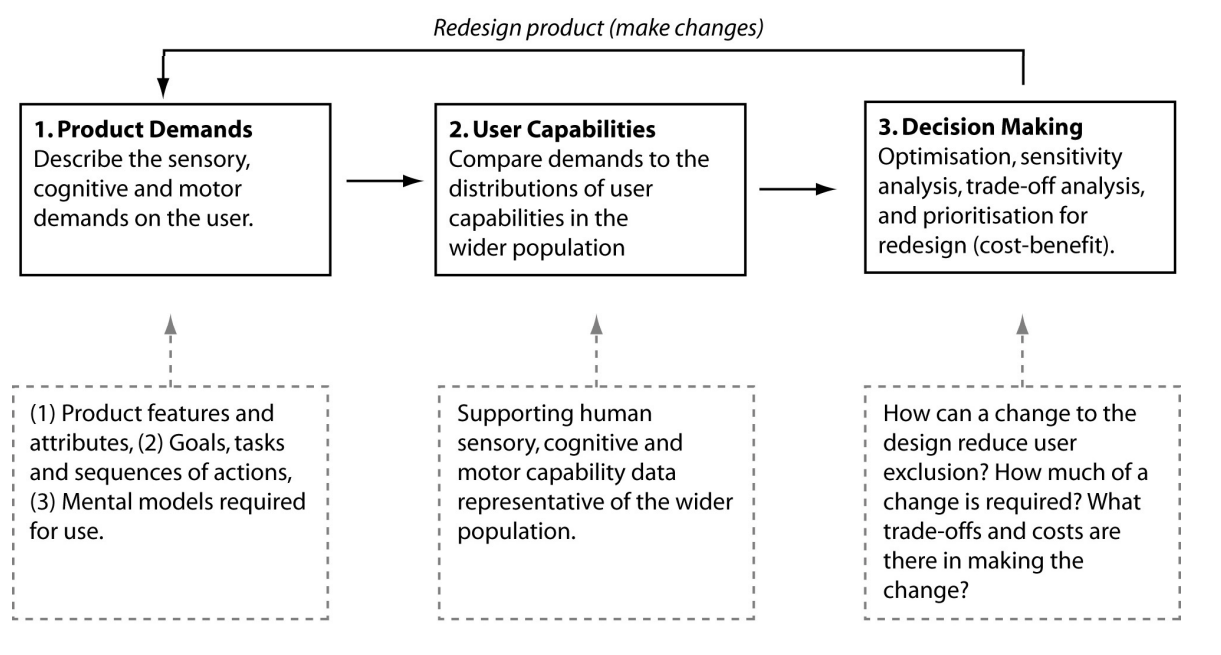

The following approach is based on the Framework for Analytical Inclusive Design Evaluation by Persad et al. Steps in the framework are:

What does the design demand of the user in terms of motor, sensory, or cognitive abilities?

To evaluate accessibility and better understand opportunities for inclusivity, identify who would be excluded from using the product based on their capabilities, such as vision, hearing, cognition, mobility, and dexterity. Use tools like the calculator or demographic statistics.

Using the collected information and analytical reasoning, decide which features are deal-breakers and which ones are unique selling points. Keep in mind regulatory standards and guidelines.

Iterate with inclusivity in mind based on the results of the analysis.

As a final step, try to include a way to continuously collect user feedback during the product lifecycle as a way to increase inclusion. Examples of these would be feedback forms or community forums, as well as collecting data from support chats. For digital products, this can help adjust the interface or functionality even after product release. For physical products, it can provide beneficial information for the next models.

The process can be viewed using the following flow diagram.

Source: Persad, U., Langdon, P., and Clarkson, P.J., 2007. A framework for analytical inclusive design evaluation. In DS 42: Proceedings of ICED 2007, the 16th International Conference on Engineering Design, Paris, France, 28.-31.07.2007 (pp. 817-818).

An example of applying an inclusivity evaluations

Consider a reusable water bottle. The following steps can be taken to evaluate the inclusivity of its design:

-

Defining product demands:

- Grip and handle design: Examine whether the bottle has an ergonomic design that makes it easy to hold for people with limited hand strength or arthritis. Look for features like textured surfaces or built-in handles.

- Opening mechanism: Assess the ease of opening and closing the bottle (e.g. button press). Consider whether the cap or lid can be operated easily by individuals with limited dexterity or hand strength. Are there one-handed operation options (is it possible to open/use with just one hand)?

- Material and weight: Analyse the material and weight of the bottle. Is it lightweight enough for children, the elderly, or individuals with physical disabilities to carry comfortably?

- Visual and tactile indicators: Check for any visual or tactile indicators that help users understand how much liquid is left in the bottle. Are there measurement markings that are easy to see and read?

- Spout or straw design: Evaluate the design of the spout or straw, if present. Is it easy to drink from without needing to tilt the bottle excessively, which could be challenging for some users?

- Cleaning and maintenance: Consider how easy it is to clean and maintain the bottle. Are all parts easy to disassemble and clean, especially for people with limited hand mobility?

-

Analyse customer abilities:

- The smooth surface might be too difficult to hold for people with significant dexterity and/or grip strength issues.

- You also need to be able to tilt the bottle considerably to be able to drink from it.

- To clean it, you would need to be able to grip it and twist the top, which poses another dexterity challenge.

- The size of the design might not be appropriate for children, as the weight of the filled bottle may be too great for them to handle, and the spout size is too big.

- Using the exclusion calculator, we can determine that for people aged 16 and above, we are excluding approximately 5% of the population from our design.

-

Review criteria:

- The bottle is mainly designed as a sports bottle, making people who exercise the primary customer base.

- By considering people with dexterity issues (permanent), we can design a better product not only for them but also for athletes who recently had an injury (temporary) or have just finished a session of heavy weightlifting and have sweaty hands with reduced grip strength due to exhaustion (situational).

- Children are not the target user, so the design does not need to include their needs.

-

Adjusting the design based on the results:

- A more profiled body would make it easier to hold; the shape itself might even be changed to incorporate a handle of sorts.

- The spout can have an interchangeable end that can be turned into a straw for users who cannot tilt the bottle.

- The lid should be more profiled to make it easier to untwist for cleaning, and the bottle can be made of dishwasher-safe plastic to allow dishwasher cleaning for users who would struggle to handwash (and those who just do not like to handwash).

- By incorporating these changes, the exclusion drops from 5% to 3.9% according to the exclusion calculator.

-

Continuous feedback loops:

- Including a review section on the website that sells the bottle allows customers to leave their feedback, which can lead to further design improvements in the future.